Basket

The Collection

See A Hidden Ulster pp. 435-67 with references and extended information.

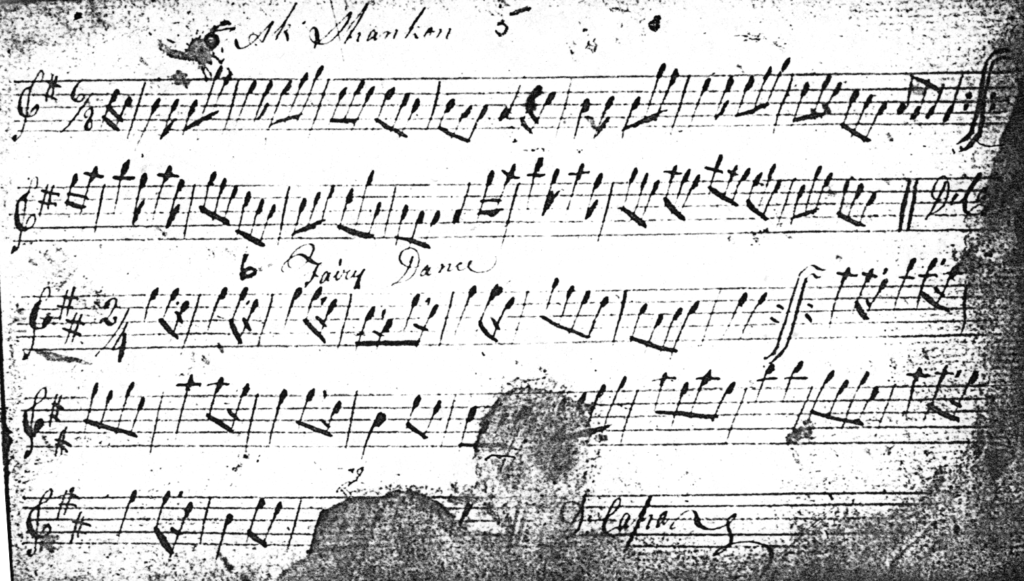

Patrick McGahon’s music manuscript dated 1817 was published for the first time in A Hidden Ulster with detailed background information (AHU 435-67). It was a rare and treasured find. Since that publication his music is sourced from the manuscript and played again by a number of local musicians. ORIEL ARTS invited fiddle player Dónal O’Connor, who is editing the manuscript, to record on film a selection of the tunes and to transcribe the music to modern notation.

Patrick McGahon was a prolific scribe of Irish language literature, who lived in Dungooley, County Louth, on the Armagh/Louth border, at the end of the eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth century. Very little else is known about his life. He was a teacher with the The Irish Society during the nineteenth century (AHU pp. 21-8). He is reputedly buried in Urney graveyard, on the Armagh/Louth border near Forkhill.

Older people in the Dungooley locality could locate the house and lane where he may have lived until it was cleared in 2012 by a local landowner.

McGahon’s manuscripts, mainly dated 1813-1845 are found in different collections and include stories and poetry in Irish, some songs in English, a notebook of mathematics and this collection of mainly dance music. One of his manuscripts in the Royal Irish Academy in Dublin (MS 24L31), written about 1822, includes a translation of Úirchill a’ Chreagáin attributed to the poet Art Mac Cumhaigh.

This music manuscript dated 1817 and later, and published for the first time in A Hidden Ulster with detailed information (AHU 435-67), is transcribed into a small hard backed book, which would fit easily into a fiddle case. The manuscript collection includes dances, marches, and a few airs of songs in English. Some or the tunes are repeated. The manuscript transcriptions show all the signs of formal training in music notation with the use of many classical musical terms. The notation gives some ornamentation details. There are age stains and fingerprint markings on many of the pages of the manuscript. All individual 106 pieces of facsimile notation have been computer cleaned by the author, for publication in A Hidden Ulster (pp. 440-67).

It is quite unique to find an Irish language scribe who also wrote down music notation and who was probably a musician too, dating from this period at the beginning of the nineteenth century. This rare collection of mainly dance tunes leaves many unanswered questions.

Where, for instance, did a scribe such as McGahon learn the skill of music notation? It is most likely that he attended the school or academy set up by the Irish language scholar, the Revd William Neilson, within a short few miles, in Clanbrassil Street in Dundalk, which welcomed pupils from all denominations?

Neilson was appointed minister to the Presbyterian congregation in Dundalk, County Louth in 1796, which was mainly Irish-speaking and where he set up an academy in Clanbrassil Street. He was the author of Introduction to the Irish Language, a unique source of the Irish of County Down. He left Dundalk in 1818 on being appointed Head of the Classical School and Professor of Classical Hebrew and Irish Languages in the Belfast Academical Institute.

Before him, in Dundalk was another minister and a friend, the Revd Andrew Bryson who was also an Irish language enthusiast, who was asked to assist with the Belfast Harpers Festival of 1792. His brother Samuel Bryson was later a director of the Harp Society, which would suggest that they were both literate in music (AHU pp. 436-7 footnotes). This Bryson/Neilson connection and their link with Dundalk and the Harper’s Convention of 1792 in Belfast, might well be the source of Carolan’s music being written down by Patrick McGahon in his manuscript of 1817.

There was an active interest, among the Presbyterian Gaelic speaking congregation in Dundalk at that time, in Irish music, and it was not unusual for ministers in the Dundalk congregation to give sermons in Irish in the hinterlands of Louth and Armagh. Dungooley, the homeplace of Patrick McGahon, is a mere seven miles from Dundalk where Neilson had his school (AHU + footnotes pp. 435-7). This is the most probable explanation for Patrick McGahon’s musical literacy.

This manuscript music in Oriel, dated 30 March 1817, was in the Laverty Collection No.15(4) in the NUI Maynooth, during research for A Hidden Ulster but it is now in the Tomás Ó Fiaich Library in Armagh. It is a collection of about 105 pieces.

It has gone relatively unnoticed by musicologists, primarily due to its location among Irish language literature manuscripts. The publication of this manuscript in facsimile form in A Hidden Ulster – people, songs and traditions of Oriel (2003) brought it to public attention, and a return of tunes to the repertoire of local musicians.

The manuscript is written in McGahon’s hand and possibly with a few tunes transcribed by one other. On the inside first page he gives his name in English ‘Pat McGahon his book’ and in Irish script he has written:

‘Sé Padruic MacGathan a (nDún)guaile sg(r)iobh an leabhair so … ndaibrail aois an Tigh(ear)na oa(ch)t ccead agus se(ach)t mblian deag, Guidh go geur an sg(r)iobhneoira … sa dhul faoi rodh go Flaitheas Dé’

It is Patrick McGahon from Dungooley who wrote this book.…, in the year of our Lord 1817. Pray intensely for the writer … and he going before God’s heaven).

Patrick McGahon

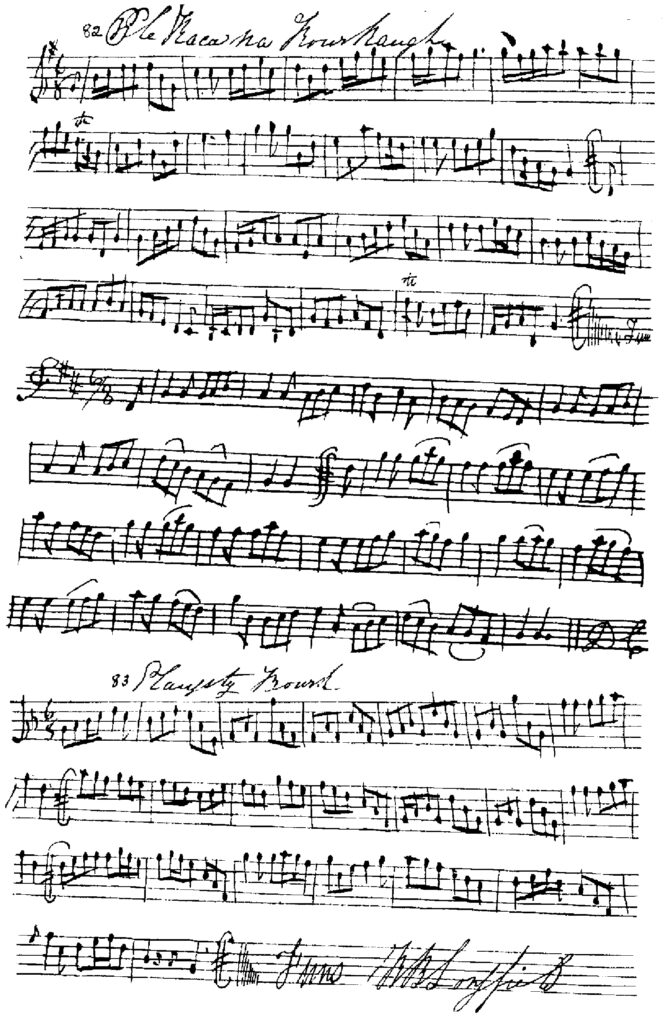

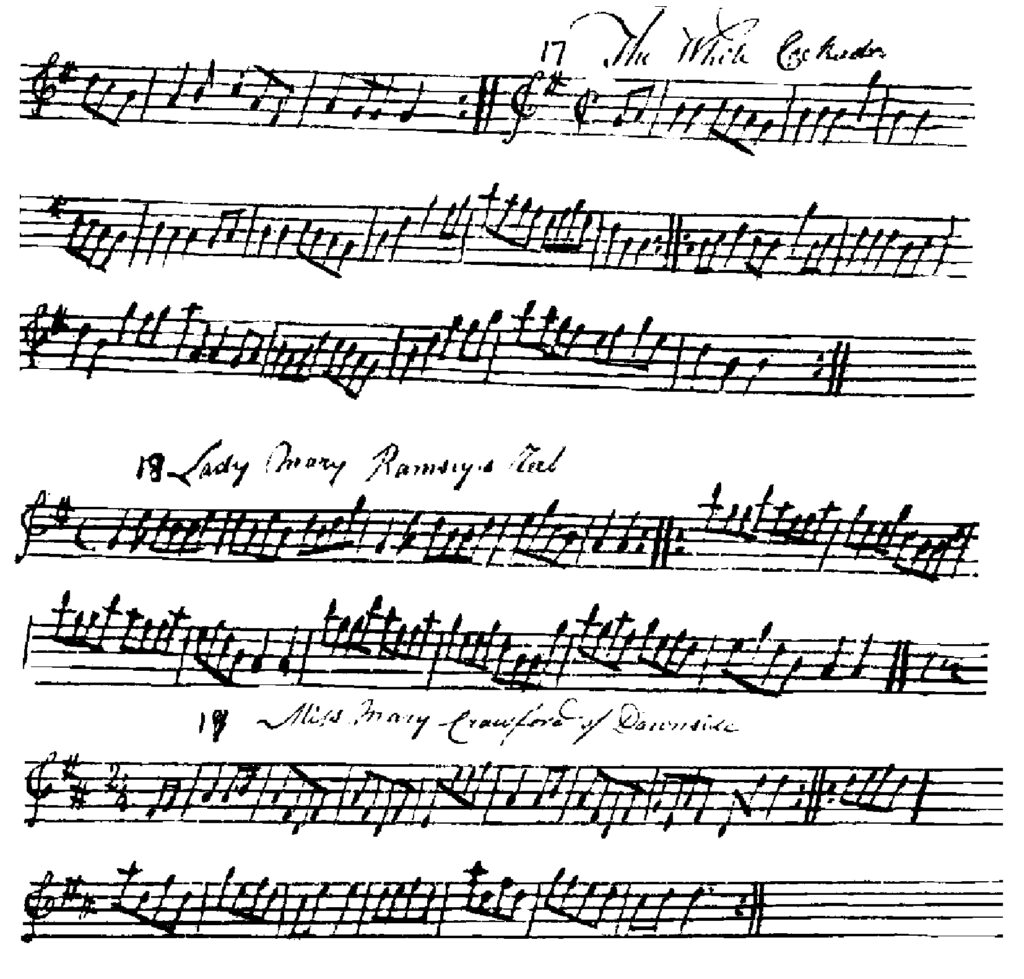

The names ‘Robert Balmer, Longfield’ and ‘Bernard Burns, Tully Donnald’ are written on a few of the sheets. Longfield is in nearby Forkhill, and Tullydonnell, as it is known, is about two miles from Forkhill in County Armagh. These two men may have been the source of some of the tunes. Following tune 41 is the note ‘Patt Traynour of Drumchree’ who may also have been another source. The signing of his name throughout the book, e.g ‘Patrick McGahon his hand’ and ‘Pat McGahon his book’ together with various notes in Irish and in English would suggest that the manuscript was for his own use. No titles are written in Irish with the exception of Puirt Alba 88b and tune 82 Ple Raca na Rourkaugh (O’Rourke’s Feast) written by Aodh Mag Shamhráin and composed by Carolan, and that itself is written in English phonetics and may not be in McGahon’s hand, as it, and the following tune, ‘Planxty Bourk’ is followed by the signature of ‘RB Longfield’. (Robert Balmer)

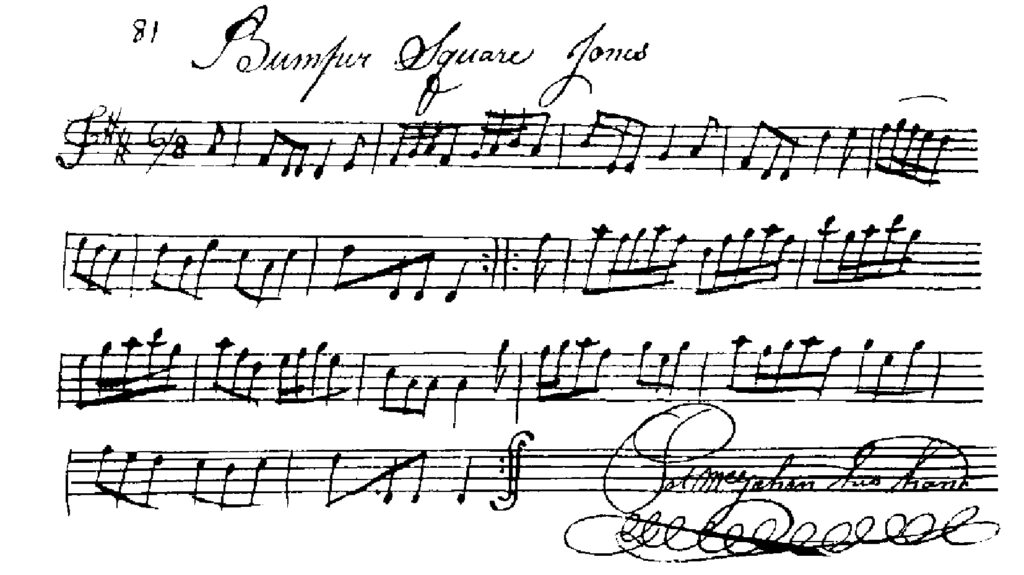

The manuscript is of additional interest as it includes tunes by the harper, Turlough O’Carolan . Of these pieces Bumper Square Jones (81) is signed by McGahon’s, followed by Ple Raca na Rourkaugh (82) and Plangsty Bourk (83). Plangsty Connor (86) is in the same hand as 82 and 83, though it is followed by two names in the same handwriting, i.e. ‘Robert Balmer, Longfield’ and ‘Bernard Burns ‘Tully Donald’ – placenames in south Armagh.

There are a number of tunes here that are associated with the name Jackson. Some of these tunes are also to be found in the Donnellan collections of dance music written down about ninety years after McGahon’s transcriptions. Many pieces are of Scottish origin, as their titles would suggest, together with the occasional note by McGahon indicating their origin e.g. ‘Calder Fair, a favorite dance, Puirt Alba’ (88b) and ‘Good Humored Reel, A Scotch air’ (53).

Some pieces are of particular interest including Copenhagen’s Waltz 89, which was clearly popular in the locality as it also reappears again, a century or so later, in the repertoire of Piper Philip Goodman who came from nearby Farney in County Monaghan (AHU 468-73).

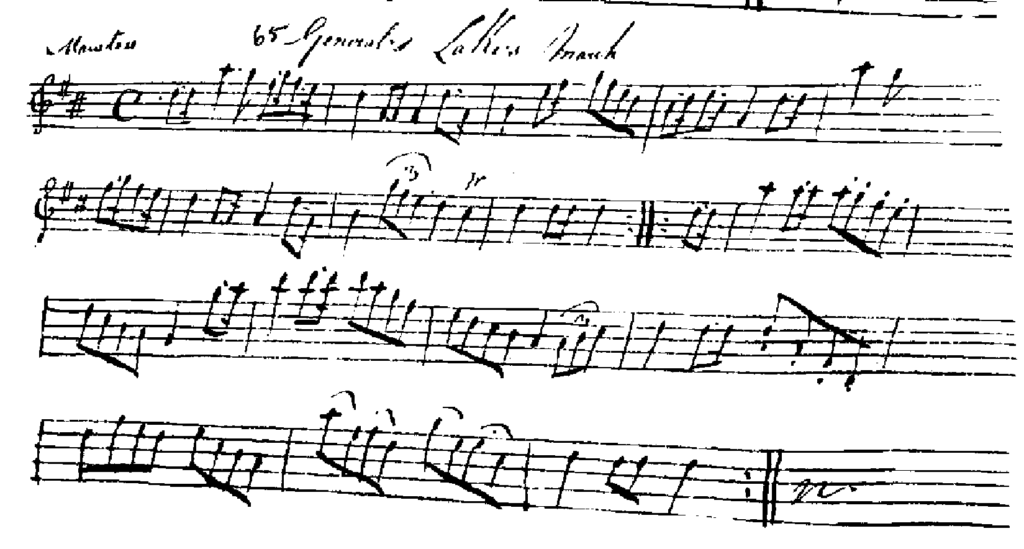

General Lake’s March (65) refers to an English general who was in County Armagh in 1797 and stayed in the local yeomanry barracks Belmont in Mullaghban, where he led a ruthless campaign throughout the north of Ireland in an effort to wipe out the Presbyterian led United Irishmen rebellion in Ulster.

In this video Dónal O’Connor plays General Lake’s March from the McGahon manuscript.

It is worth noting that within a short twenty years, a piece of music named after General Lake was being transcribed by a local Gaelic scribe named Patrick McGahon (Pádraig Mac Gatháin), in nearby Forkhill, who had lived within a few miles of Belmont Barracks throughout the period of those atrocities.

Music Manuscripts

The full Patrick McGahon Music Manuscript of 105 tunes is reproduced in facsimile in A Hidden Ulster on pp. 440-67. The original was not up to publication standard at Four Courts Press publishing, and so, in order that it would be published, and to reach a wider audience, the author cleaned each set piece by computer eraser.

McGahon included some words in English in the manuscript, which are not reproduced in the published facsimile in A Hidden Ulster pp. 440 -67.

The following amendments to the title list of tunes in the collection and a general commentary on the collection was contributed by fiddle player Seamus Sands to the ORIEL ARTS PROJECT in 2017:

Having explored many manuscripts and collections pre-dating McGahon’s 1817 manuscript, I suggest that a significant proportion of the tunes that McGahon included were drawn from earlier published sources, and not from performing musicians.

One of his main sources, I suggest, was the O’Farrell Pocket Companion volumes (c.1806) and closer inspection of some of the tunes common to both O’Farrell and McGahon show some interesting patterns. The Jackson tunes, in particular, are worth comment.

In McGahon’s No.71 Humours Of Glen’ his notation is an exact copy of O’Farrell’s version. In fact, even the sharp note in bar 3 and the rolled B in the 3rd bar of the 2nd part are identical. Likewise, the “slow” time reference above the tune is also there in O’Farrell. Most of McGahon’s tunes do not include such guidance, so it probably doesn’t appear there above this tune as his standard practice.

No.72 ‘Jackson’s Maid at the Fair’ is also identical to O’Farrell and interestingly McGahon also denotes the tune as “Irish” adjacent to the title, again something from O’Farrell, and not practiced by him in the majority of the other tunes he includes. No.73 ‘Jackson’s Welcome Home’ also mirrors O’Farrell as does No.75 ‘Jackson’s Coge in the Morning’. In the latter tune in the 2nd bar of the 2nd part there is a high C note, which again is identical to O’Farrell. If transcribed from a musician it is more likely that such an ‘awkward’ note would have been changed in some way, depending on the instrument involved, or perhaps the key would have been changed for the tune.

To further illustrate the suggestion, No.76 ‘Thousands of Bottles I’ve Cracked in my time’ includes two grace notes in the first half of the tune. Again, the tune as notated is identical to O’Farrell and even the two grace notes are mirrored.

While these examples may support the suggestion that O’Farrell was most likely a source for McGahon, it is also interesting that some tunes that McGahon includes, that also appear in O’Farrell, are actually different versions and more closely match other manuscripts, including Lee, Himes, and others from the 1770s to around 1810. In some cases I’ve found only a difference of a run of three notes replacing two, or similar small changes, or the music transcribed into a different key. This may open the door to the possibility that McGahon made small changes to some of his sourced tunes to make them more appealing, easier to play, or perhaps easier to teach.

Facsimilies

Manuscript facsimiles of the following list of music pieces are published in A Hidden Ulster pp. 440-67.

- The Maid of Lodie

- The Dutch Skipper

- Merrily Dance the Quaker’s Wife

- The Way Worn Traveller

- Ath Shankon ?

- Fairy Dance

- I Was a Beauty Then

- When I Was Young

- Crazy Jean

- The Bard’s Legacy

- Neil Gow’s Second Wife Again

- Paddy O’Carroll

- Scotch Reel

- Kitty of Coleraine

- Pandian Air

- Pandian Air

- The White Cockade

- Lady Mary Ramsey’s Reel

- Miss Mary Crawford of Downside

- The Boyne Water

- Hey my Nancy

- Sir David Hunter Blair’s Reel

- The Spinning Wheel

- The Boyne water

- Battle of the Nile

- Rambling Kitty

- Soldier Laddy

- The Young Man’s Dream

- Off She Goes

- The Piper Over the Meadow Straying

- Donald Mc Donald

- Sprig of Shilila

- Lady Harriot Lee’s Waltz

- Jenny Put the Kettle On

- Molly Astore

- The Freemason’s March

- Dance in the Hony Moon

- Neil Gow

- Mrs Casey

- (Over?)Young to Marry Yet

- Battle of the Boyne

- Air in the Travellers

- Speed the Plough

- Jackson’s Bottle of Punch

- Raslin Castle

- Song in Peeping Tom of Coventry

- The Bonniest Lass in all the World

- Nelson’s Victory

- Hunt’s March

- The Lady of Lathe

- Lewes Gordon (with words)

- Patrick’s Day

- Good Humoured Reel – A Scotch Air

- In Paddy’s Love

- The Rose Tree in Full Bearing

- Trip to the Cottage – with words following

- Poor but Honest Soldier

- The Flower of Edinburgh

- My Lodging is on the Cold Ground

- Humming – Song by Mr R.P. ‘What a Beauty I did Grow’ with words

- Jackson’s Morning Brush

- Jackson’s Bottle of Claret

- Jackson’s Bottle of Punch

- Patrick’s Day

- General Lake’s March

- The Irish Jigg

- Richer’s Hornpipe

- Neil Gow

- Jacksons’Dream

- If ever I Marry I am a Son of a Whore

- The Humours of Glin

- Jackson’s Maid at the Fair –Irish

- Jackson’s Welcome Home

- Hornpipe

- Jackson Goes in the Morning

- Thousands of Bottles I’ve Cracked in My Time (Savourneen Dhylish)

- The Ale Wife and her Barrell

- He Took from me my wife Yestreen

- The Ladies Pantaloons

- Miss S. Treby’s Hornpipe

- Bumper Square (sic)Jones

- Ple Raca na Rourkaugh (sic)

- Plangsty Bourk

- Drunk at Night

- Paddy Carey

- Plangsty Connor

- The Wind That Shakes the Barley followed by script by McGahon in Irish

- The Lady of the lake

88(b) Calder Fair – a favourite Dance – Puirt alba… - Copenhagan’s Waltz

- Lady Hope’s Favourite Reel

- The Dusty Millar

- Morgiana in Ireland

- Mrs Mc Lood – a favourite Dance

- The Fairy dance

- Dance in Tekele

- Lochaber

- Lovely Sweet Jessie the Flower of Dunblain

- Lady Charliott Lee’s Waltz

- Boneparte’s Retreat to the island of Alba followed by some words

- The Girl I left Behind Me

- Aldridge’s Hornpipe

- The Duke of Bedford’s Fancy

- What a Beauty I did Grow

- God Save the King

- What a Beau my Granny Was

Amendments to the above list by fiddler Séamus Sands include the following:

- No.3 “Merrily Dance the Quaker’s Wife” should read “Merrily Danced the Quaker’s wife”

- No.5 “Ath Shankon ?” should read “Ap Shenkin” (ref. E.Lee Collection, Dublin, c.1808)

- No.34. “Jenny Put the Kettle On” should read “Jenny Put the Kettle Down”

- No.40 It should read “Over young to marry yet”

- No.66 “The Irish Jigg”… believed to be an old version of the well-known slip jig tune “Drops of Brandy”

- No.71 “Humours of Glin” should read “Humours of Glen” (ref. O’Farrell)

- No.75 “Jackson Goes in the Morning” should be “Jackson’s Coge in the morning”

- No.91 “Dusty Millar” should be “Dusty Miller”

- No.95 “Dance in Tekele” should be “Dance in Tekeli”

- No.105 should be “What a Beau my Granny Was”